"Transsexuals... become castrati,

extol this operation as a liberation"

Piotr O. Scholz

Eunuchs and Castrati

extol this operation as a liberation"

Piotr O. Scholz

Eunuchs and Castrati

*************************************

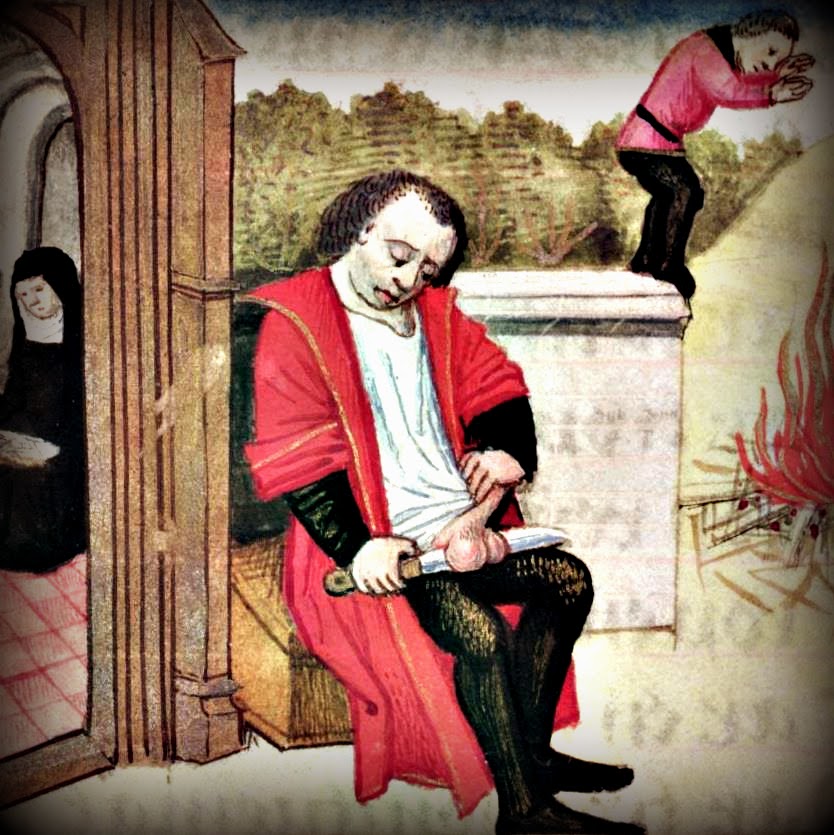

“The trans-historical focus of most works on castration,” notes Matthew Kuefler, “reminds us that eunuchs in medieval European society had a history stretching back much further than the beginning of the Middle Ages.”[i] The same goes for the modern transsexual, I argue. A genealogy of surgery can be traced via the scar tissue of castrates with an archeological record of skin from a doctor’s office in 21st century America, through medieval Europe and beyond, demonstrating that the violence of laying hands on another is not accidental in the evolution of surgery but congenital to its cultural work.[ii] Since Classical medicine, surgery has operated by coding certain bodies as “the parts” (that which is discarded), while coding others as “the whole” (that which is preserved).[iii] A progressive history of a body is made by eliminating the prior for the sake of the later. In the case of castration, testicles, and sometimes phalluses, were cut off in what began as a cure for illness or wounds but became a way of controlling spiritual and temporal life.[iv]

Before spread of castrates throughout Europe in the form of eunuchs and castrati, the act of castrating a servant to produce specific changes, e.g. making him sterile or keeping his voice from dropping, was an operation that cut across cultural boundaries. Adopting by Byzantium from the Greco-Romance, when various Muslim states claimed the region, the practice of utilizing eunuch servants were adopted and spread throughout conquests in Asia and Eastern Europe.[v] The job of enslaving and surgically producing eunuch servants, however, largely fell to Christians, particularly monasteries, who collected, castrated, and sold eunuchs.[vi] The work of these operations on and through these slaves moved around the Mediterranean encouraging the spread not only physical surgery but social practices aimed to erase old sexual, national, and religious identities.[vii]

*************************************

Because he could not create his own line of heirs and was thus dissuaded from attempting to amass large stores of personal wealth, the eunuch was considered a safe trustee for the Lord’s possessions, managing servants, the estate, armies and Churches.[x] The castrate was used not only to police gender politics between wife and husband, but this liminal position made the castrate at once the mechanism of cultural erasure and the keeper of the socially divided parts of the community. Administrators of the Latin Church soon discovered the castrate’s instrumental social value in managing sex and temporal politics. By the late middle ages, as high voiced castrati were being integrated into choirs of Rome, the castrate had come to represent a body several times denied, lingering only as unseen singers and prayers to serve the futurity and salvation of others.

While medical doctors enacted the physical violence, Doctors of the Church, such as Peter Abelard, were instrumental in making castrates into tools for spiritual operations. While Abelard’s castration followed closer to the line of being “made that way by men,” her drew on Mathew 19:12 to encourage chastity, where penitents literally or figuratively “make themselves eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven.”[xiv] Since the medieval period, interpretations of this passage find a renunciation of one’s body, sexual identity, and past for the sake of purifying closure, erasing the sexual abilities of the castrate. Thus, despite continued erotic correspondence with Louise, Abelard wrote that castration freed him to pursue a heavenly eternity unencumbered by demands to think temporally about gender and sexuality.[xv] The violence on Abelard cut deep, internalizing a sense of division and making him an advocate for the development of more such operations.

*************************************

By the late Middle Ages, medical, legal, and spiritual surgeries were inextricable, working in congress under “Christus Medicus” (Christ as Physician) or “oure soules leche” as the Pardoner names Him.[xvi] Drawing on the cures and teachings of Jesus, such as Mathew 18:9, “if your eye causes you to stumble, gouge it out and throw it away,” and Matthew 19:12, this doctrine could be used to excuse Christians to lay hands on another if the violence could be justified as promoting the spiritual health of a person or society.[xvii] “The opinion of ancient science that castration,” Mathew Kuefler notes, “could cure or at least alleviate ailments also made its way into medieval science.” Despite religious prohibitions against deforming the integrity of a body, castration, was “permissible mutilation if used to save the whole person.”[xviii] With the castrate as a sign of a purged past, society could excuse a wide array of violent operations including producing eunuchs in monasteries, purging Byzantium and the Holy Land, and castrating prisoners.[xix]

A brief history such as this is insufficient to account for the tiniest part of the lives captured in the social operation of sharp machines, but can at least testify that in the scars of castrates we find a genealogy implications not only on the development of sex change operations but a wide array of physical and social partitioning of bodies across time. Beyond eunuchs and castrati, castration has developed into the surgical and chemical sterilization of racial minorities and people with disabilities.[xx] The reconstruction of genitals continues to police gender through circumcision, genital mutilation, and operations on intersex children.[xxi] Punitive surgery has served as precedent for later legal and social violence, “corrective” rape, and the internalized shame that prompts suicide.[xxii] A critical trans history of the scars of castration cannot be limited to the castrate but all those bodies on and through whom the violence of sharp machines operates.

A brief history such as this is insufficient to account for the tiniest part of the lives captured in the social operation of sharp machines, but can at least testify that in the scars of castrates we find a genealogy implications not only on the development of sex change operations but a wide array of physical and social partitioning of bodies across time. Beyond eunuchs and castrati, castration has developed into the surgical and chemical sterilization of racial minorities and people with disabilities.[xx] The reconstruction of genitals continues to police gender through circumcision, genital mutilation, and operations on intersex children.[xxi] Punitive surgery has served as precedent for later legal and social violence, “corrective” rape, and the internalized shame that prompts suicide.[xxii] A critical trans history of the scars of castration cannot be limited to the castrate but all those bodies on and through whom the violence of sharp machines operates.

*************************************

Part 1: A Physician's Tale

Part 3: The Trans-Operative

Part 4: The Physician's Surgery

Part 5: The Pardoner's Scars

*************************************

*************************************

Part 1: A Physician's Tale

Part 3: The Trans-Operative

Part 4: The Physician's Surgery

Part 5: The Pardoner's Scars

*************************************

*************************************

[i] Matthew S Kuefler. “Castration and Eunuchism in the Middle Ages.” Handbook of Medieval Sexuality. Vern L Bullough and James A Brundage ed. N. Y.: Routledge, 2000. 280.

[ii] “Emasculated men, usually described incorrectly as eunuchs, can now be found among transvestites, transsexuals, and other members of various sects … Some who consider themselves transsexuals in the West, although they have actually become castrati, extol this operation as a liberation.” Piotr O. Scholz. Eunuchs and Castrati: A Cultural History. John A Broadwin and Shelley L Frisch trans. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers, 1999. 3, 234.

[iii] Taylor, Gary. Castration: an Abbreviated History of Western Manhood. New York: Routledge, 2000. 56. Kuefler. “Castration and Eunuchism,” 286. Also cited in Tracy, Larissa. “A History of Calamities: the Culture of Castration.” Castration and Culture in the Middle Ages.5.

[iv] Tracy, “A History of Calamities,” 5-18; Matthew S Kuefler. “Castration and Eunuchism,” 286.

[v] Scholz, Eunuchs and Castrati,198. Tougher, Shaun. The Eunuch in Byzantine History and Society. N.Y.: Routledge, 2008. 60-65, 119.

[vi] The castration of eunuchs was a production that was often forbidden and often ignored, with producers and slave-traders, often buying their eunuchs from foreign sources. See: Scholz, Eunuchs and Castrati,198-199. Kuefler. “Castration and Eunuchism,” 284-290.

[vii] Scholz, Eunuchs and Castrati, 203-214, 232. Kuefler. “Castration and Eunuchism,” 280; Tougher, The Eunuch in Byzantine History and Society, 60-67, 119.

[viii] Taylor, Gary. Castration, 33; Tracy, “A History of Calamities,” 6. Scholz, Eunuchs and Castrati, 232.

[ix] Tracy, “A History of Calamities,” 4-11. Taylor, Castration, 33-36; Kuefler. “Castration and Eunuchism,” 282-285.

[x] Tougher, The Eunuch in Byzantine History and Society, 54-82. Taylor, Castration, 32-39. Kuefler. “Castration and Eunuchism,” 282-292. Tracy, “A History of Calamities,” 4-9. Scholz, Eunuchs and Castrati, 200-209.

[xi] Peter Abelard’s castration has been the topic of numerous articles and chapters. Irvine, Martin. “Abelard and (Re)Writing the Male Body: Castration, Identity, and Remasculinization.” 87-106; Wheeler, Bonnie. “Origenary Fantasies: Abelard’s Castration and Confession.” 107-128; Ferroul, Yves. “Abelard’s Blissful Castration.” 129-150. Becoming Male in the Middle Ages. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen and Bonnie Wheeler ed. N.Y.: Gardland Publishing, Inc., 2000; Tracy, “A History of Calamities,” 9-19; Tougher, The Eunuch in Byzantine History and Society, 11; Scholz, Eunuchs and Castrati, 246-255; Kuefler, “Castration and Eunuchism,” 289-290.

[xii] Numerous scholars discuss both the use and resistance to the punitive use of castration in European law: Kuefler, “Castration and Eunuchism,” 287-289; Tracy, “A History of Calamities,” 19-28; Irvine, “Abelard and (Re)Writing the Male Body,” 96-99; Bremmer Jr, Rolf H. “The Children He Never Had; the Husband She Never Served: Castration and Genital Mutilation in Medieval Frisian Law.” Castration and Culture in the Middle Ages. 108-130; Taylor, Gary. Castration,52-55.

[xiii] Johansson, Warren and William A Percy, “Homosexuality. ” Handbook of Medieval Sexuality. 168-175; Tracy, “A History of Calamities,” 19-24; Kuefler. “Castration and Eunuchism,” 286-290.

[xiv] Scholz, Eunuchs and Castrati, 160-164. Kuefler. “Castration and Eunuchism,” 282-286. Tracy, “A History of Calamities,” 12-13.

[xv] Irvine, “Abelard and (Re)Writing the Male Body,” 87-106; Wheeler, “Origenary Fantasies,” 107-128; Ferroul, “Abelard’s Blissful Castration,” 129-150; Tracy, “A History of Calamities,” 9-19; Tougher, The Eunuch in Byzantine History and Society, 11; Scholz, Eunuchs and Castrati, 246-255; Kuefler, “Castration and Eunuchism,” 289-290.

[xvi] oure soules leche” Chaucer, “The Pardoner’s Tale,” 916. For more on Christ as Physician see: Arvesmann, Rudolph. “The Concept of ‘Christus Medicus’ in St Augustine.” Traditio. Vol. 10. N.Y.: Fordham University, 1954. 1-28.

[xvii] Matthew Taylor, Castration, 72; Tracy, “A History of Calamities,” 9-10; Kuefler, “Castration and Eunuchism,” 282-283; Tougher, The Eunuch in Byzantine History and Society, 68-82; Scholz, Eunuchs and Castrati,159-164.

[xviii] Kuefler. “Castration and Eunuchism,” 286. Also cited in Tracy, “A History of Calamities,” 5.

[xix] Castration and violent operations tended to work in junction and reflect a wide variety of social contests over bodies, property, and beliefs, while rarely gaining the status of becoming a standard response. As Tracy notes, “The desire to use castration as a way of stamping out foes undermines notions of inherited right and suggest a deeper instability within power structures. Like torture, castration is a weapon employed by the weak: those hose hold on power is tenuous or questionable,” Tracy, “A History of Calamities,” 19-24. See also: Tougher, The Eunuch in Byzantine History and Society, 119-127; Scholz, Eunuchs and Castrati, 198-234.

[xx] For more on the sterilization of racialized and disabled persons see: Mitchell, David and Sharon Snyder. Cultural Locations of Disability. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006. Chesterton, G. K. Eugenics and Other Evils: An Argument against the Scientifically Organized State. Ed. Michael W. Perry. Seattle: Inkling, 2000. Print. Lewis, C. S. "The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment." God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1970. 287-300. Print.

[xxi] Numerous debates on circumcision continued throughout the middle ages and after, as noted by Kuefler, “Castration and Eunuchism,” 184. Intersex surgery on hermaphrodite/intersex children were in regular use, they were conceptually folded in as “eunuchs from birth” and continue today: see, Tougher, The Eunuch in Byzantine History and Society, 31-32; Kuefler, “Castration and Eunuchism,” 286; Scholz, Eunuchs and Castrati, 5-13; Chase, Cheryl “Hermaphrodites with Attitude: Mapping the Emergence of Intersex Political Activism,” The Transgender Studies Reader, 300-314; Winkerson, Abby L. “Normate Sex and Its Discontents.” Sex and Disability. Robert McRuer and Anna Mollow ed. London: Duke, 2012. 183-207.

[xxii] See Raymond, Janice. “Sappho by Surgery: the Transsexually Constructed Lesbian-Feminist.” The Transgender Studies Reader. 134; Winkerson, “Normate Sex and Its Discontents,” 183-207.

*************************************

https://bayanlarsitesi.com/

ReplyDeleteGöktürk

Yenidoğan

Şemsipaşa

Çağlayan

WJRMML

Batman

ReplyDeleteArdahan

Adıyaman

Antalya

Giresun

SZB3G

görüntülü show

ReplyDeleteücretlishow

B1DK

Çorlu Lojistik

ReplyDeleteManisa Lojistik

Eskişehir Lojistik

Afyon Lojistik

Konya Lojistik

40YF

D229B

ReplyDeleteAdana Evden Eve Nakliyat

Manisa Evden Eve Nakliyat

steroid cycles for sale

Çankırı Evden Eve Nakliyat

Silivri Fayans Ustası

Samsun Evden Eve Nakliyat

turinabol for sale

Bursa Evden Eve Nakliyat

buy masteron

DA06F

ReplyDeleteÇerkezköy Oto Elektrik

Antep Evden Eve Nakliyat

Ardahan Şehir İçi Nakliyat

Samsun Evden Eve Nakliyat

Batman Şehirler Arası Nakliyat

Çerkezköy Koltuk Kaplama

Kayseri Şehirler Arası Nakliyat

Samsun Şehirler Arası Nakliyat

Çerkezköy Parke Ustası

EAABA

ReplyDeleteOrdu Şehir İçi Nakliyat

Çanakkale Parça Eşya Taşıma

Çanakkale Lojistik

Coinex Güvenilir mi

Bayburt Evden Eve Nakliyat

Pursaklar Boya Ustası

Tekirdağ Parça Eşya Taşıma

Çorum Parça Eşya Taşıma

Çerkezköy Kombi Servisi

8E323

ReplyDeleteorder oxandrolone anavar

order steroid cycles

Çerkezköy Boya Ustası

buy turinabol

Çorum Evden Eve Nakliyat

order fat burner

Tunceli Evden Eve Nakliyat

Urfa Evden Eve Nakliyat

order testosterone propionat

0616A

ReplyDeleteKırıkkale Parça Eşya Taşıma

Elazığ Evden Eve Nakliyat

Mersin Lojistik

Hakkari Evden Eve Nakliyat

Tunceli Şehirler Arası Nakliyat

Elazığ Şehir İçi Nakliyat

Erzurum Şehirler Arası Nakliyat

Silivri Duşa Kabin Tamiri

Tekirdağ Parke Ustası

Ouch

ReplyDeleteMy genitals are to large to remove!

ReplyDelete0F232

ReplyDeleteartvin sesli sohbet odası

manisa mobil sohbet odaları

sakarya telefonda canlı sohbet

kütahya canlı sohbet siteleri ücretsiz

erzincan sesli sohbet mobil

diyarbakır ücretsiz sohbet uygulaması

van kadınlarla görüntülü sohbet

çankırı yabancı görüntülü sohbet uygulamaları

kilis telefonda görüntülü sohbet

BEC79

ReplyDeletedenizli parasız sohbet

bartın ücretsiz sohbet uygulaması

niğde canlı görüntülü sohbet siteleri

yozgat yabancı canlı sohbet

erzurum canlı sohbet

canlı görüntülü sohbet

görüntülü sohbet kadınlarla

siirt görüntülü sohbet ücretsiz

Kastamonu En İyi Ücretsiz Sohbet Uygulamaları

9C8A6

ReplyDeleteKripto Para Nedir

Görüntülü Sohbet Parasız

Jns Coin Hangi Borsada

Kripto Para Kazma Siteleri

NWC Coin Hangi Borsada

Mexc Borsası Güvenilir mi

Bitcoin Para Kazanma

Dlive Takipçi Satın Al

Threads Beğeni Satın Al

F2E59

ReplyDeletedao maker

debank

DefiLlama

pancakeswap

uniswap

yearn finance

zkswap

avalaunch

poocoin

Ok see you later tonight and let me know if we are still together or not alone and not just the same way to be

ReplyDeleteB07B1

ReplyDeletebinance referans kimliği nedir

binance

kripto para haram mı

sohbet canlı

September 2024 Calendar

bitcoin ne zaman çıktı

kucoin

bitcoin nasıl oynanır

https://toptansatinal.com/

1E3F8

ReplyDeletegörüntülü sanal show

32EE623ACE

ReplyDeletedelay

geciktirici

stag

green temptation

sinegra

performans arttırıcı

lifta

ereksiyon hapı

degra

3F35579816

ReplyDeletevigrande

lady era

whatsapp görüntülü show güvenilir

ücretli show

novagra

skype şov

kamagra

lifta

ücretli şov

06519D1273

ReplyDeleteviga

sildegra

novagra

kamagra

stag

telegram show

performans arttırıcı

fx15

lady era

1588CB8CB7

ReplyDeleteereksiyon hapı

skype şov

geciktirici

canli cam show

degra

green temptation

themra macun

sertleştirici

delay

AC52EE30D4

ReplyDeletefx15 zayıflama hapı

kaldırıcı hap

stag

cam şov

novagra hap

performans arttırıcı

kamagra hap

görüntülü şov whatsapp numarası

lady era hap

71709FEFF5

ReplyDeleteskype şov

themra macun

whatsapp ücretli show

performans arttırıcı

stag

ücretli şov

sildegra

lifta

fx15 zayıflama hapı

CB08CCBC90

ReplyDeleteinstagram beğeni satın al

A3D1E158C8

ReplyDeletetakipçi almak

CC967928CC

ReplyDeletemobil ödeme takipçi satın al

Lords Mobile Promosyon Kodu

Free Fire Elmas Kodu

M3u Listesi

Free Fire Elmas Kodu

War Robots Hediye Kodu

Avast Etkinleştirme Kodu

PK XD Elmas Kodu

Razer Gold Promosyon Kodu

B83F4A504B

ReplyDeletekadın takipçi satın al

Razer Gold Promosyon Kodu

M3u Listesi

M3u Listesi

Pasha Fencer Hediye Kodu

Online Oyunlar

War Robots Hediye Kodu

Happn Promosyon Kodu

Lords Mobile Promosyon Kodu

thanks for the content,nice blog i really appriciate your hard work keep it up. also visit for super fast

ReplyDeletehelp links

Comprar carta de condução

915323C2D2

ReplyDeleteEn İyi Telegram Coin Botları

En İyi Telegram Para Kazanma Botları

Telegram Para Kazanma Grupları

En İyi Telegram Airdrop Botları

Telegram Güvenilir Madencilik Botları

75BD25B109

ReplyDelete-

-

kusadasiguide.net

-

-

A45CB74A14

ReplyDeleteyeni mmorpg

sms onay

güvenilir mobil ödeme bozdurma forum

takipçi satın alma

-

14F0B7D23F

ReplyDeleteen iyi mmorpg oyunlar

telegram sms onay

turkcell mobil ödeme bozdurma

instagram takipçi satin alma

-

FBEB7B036C

ReplyDeletehacker arıyorum

hacker kirala

tütün dünyası

-

-

https://gatitosparaadopcion.com

ReplyDelete280935DA43

ReplyDeleteOyun dünyasında farklı türleri keşfetmek oldukça heyecan vericidir. Özellikle, mmorpg oyunlar, geniş açık dünyaları ve çok oyunculu özellikleri ile dikkat çekiyor. Bu türdeki oyunlar, uzun saatler boyunca süren maceralar ve keşif imkanı sunarak oyunculara benzersiz deneyimler yaşatıyor. Eğer yeni bir oyun arıyorsanız, bu kategorideki seçeneklere göz atmanız faydalı olacaktır.